Building the Palazzo: An Interview with Madeleine Martiniello

Critics Campus 2021 participant Vyshnavee Wijekumar speaks to Palazzo di Cozzo director Madeleine Martiniello about Franco Cozzo’s legacy, community and the changing face of Melbourne.

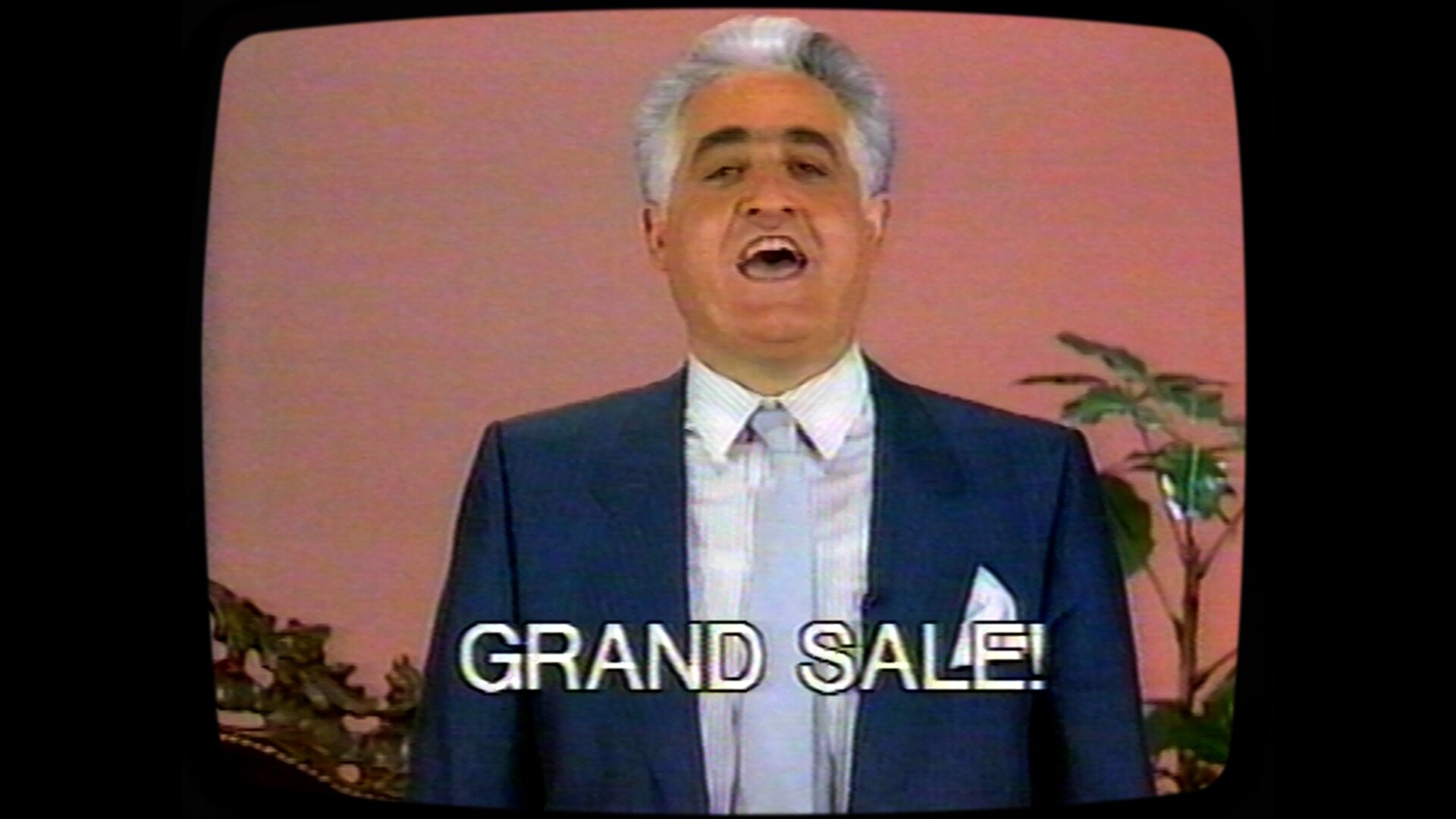

Madeleine Martiniello, director and writer of Palazzo di Cozzo, first encountered Franco Cozzo through the 1980s television advertisements for his furniture stores. “Grand sale! Grand sale! Megalo! Megalo!” he spruiked. These words defined his public persona and immortalised the thickly Sicilian pronunciation of ‘Footscray’ and ‘Brunswick’ in Melbourne’s vernacular.

Cozzo, now 85, is of the same generation as Martiniello’s Italian grandparents. “I thought to myself: why hasn’t anyone told this story? I felt like I already understood a lot about him, given our shared Italian heritage,” says Martiniello. “As a result, I was able to build trust with him as a subject.”

Palazzo di Cozzo is Martiniello’s first feature film, following on from an undergraduate degree in journalism and a Master of Film and Television (Documentary) at the Victorian College of the Arts. For Martiniello, an avid MIFF attendee from a young age, her documentary’s inclusion in MIFF 69 is a dream come true.

Martiniello acknowledges that Cozzo trusting her with his story was a big step, and contextualising it within 1950s postwar European migration in Australia was vital: “Early on, I decided that Franco would tell his story in his own words, particularly in Italian. I also wanted illustrate that he existed in a historical wave of migrants who came here and built new lives.” Through archival footage, Martiniello demonstrates that Cozzo’s most significant impact came at the height of television broadcasting, when content was still Anglocentric (indeed, multicultural broadcaster SBS was only founded in 1978). His memorable Italian-language advertising and music variety show Carosello brought cultural connection to the Italian diaspora.

“He’s this innovative figure, but influential at a time and place in Australian history that allowed him to fully express who he was. His audacious character enabled his meteoric rise and entry into the pop-culture sphere of Melbourne,” says Martiniello.

Cozzo is a natural-born performer, something he aspired to from a young age. But it wasn’t just Cozzo’s larger-than-life personality that drew Martiniello to tell this story; it was the cinematic aesthetic of his signature baroque furniture. According to the documentary, this artisanal craftmanship was prevalent in churches and aristocratic buildings throughout Italy in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was important to Martiniello to employ cinematographic techniques that elevated this design.

Given Cozzo’s 65 years in Australia, there was plenty of story and archival material to work with. Martiniello admits that her editor, Rosie Jones, had a huge remit in combining archival footage, cinematic shots and observational interviews into a cohesive story. Though she wasn’t able to shoot Cozzo in Italy due to COVID, she was able to film the factory craftsman during a holiday the previous year.

Palazzo di Cozzo

Cozzo’s legacy goes beyond the man himself – it’s also about those who revere him. Martiniello wanted to ensure she profiled the Italian families that invested in Cozzo’s goods and, to this end, set up Gumtree notifications to inform her of anyone selling his furniture. This is how she met Gianna and Serge Di Natale, who have a family history in tailoring and an eye for design.

“Gianna and Serge’s mother had recently passed away, so they were selling her belongings,” explains Martiniello. “I love this scene so much because of the emotional connection to their parents and how much they saved to buy the furniture as working-class migrants. As Sicilians, [Cozzo’s] story had cultural significance for them.”

Cozzo is treated as a minor celebrity in Footscray. During the making of the documentary, passers-by would come in and take spontaneous photos with him. Following the Western Bulldogs’ 2016 Australian Football League (AFL) win, there were people lining up outside Cozzo’s Footscray store to get selfies with him, almost as a premiership ritual.

However, at times, she did wonder: is this the real Franco Cozzo? It was clear Cozzo was comfortable in front of the camera, but, according to Martiniello, there was no duplicity. Her focus on observational filming enabled her to capture small moments to draw insight into his character. She also wasn’t afraid to ask the hard questions, including querying rumours of the store being a drug front.

“The real Franco is there – the true performer he wanted to be as a child, but also the vulnerable older man in the present,” states Martiniello. “You don’t always get that from the first encounter; it takes years of building a trusting relationship. It’s up to audiences to interpret what the subject says about themselves.”

At the core of the documentary, Martiniello wanted to celebrate Cozzo’s legacy while simultaneously documenting his challenges. Over the years, new waves of migration and growing commercial and residential development have shifted the demographic of Footscray, which Martiniello saw firsthand over the four years of shooting. Cozzo’s business hasn’t evolved, but he will always remain a Melbourne icon – his entrepreneurialism and cultural cachet have been memorialised in a major mural by local artist Heesco.

“Franco is this emblem of success for migrants who created meaningful lives here in Australia, as well as those who own his furniture,” Martiniello concludes. “It’s not just about him; it’s the extended story of what made Footscray and Melbourne what it is today.